1

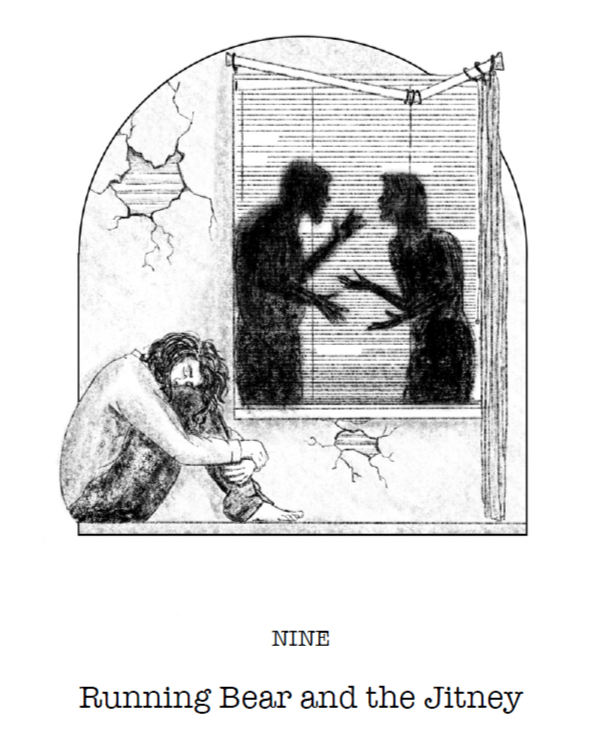

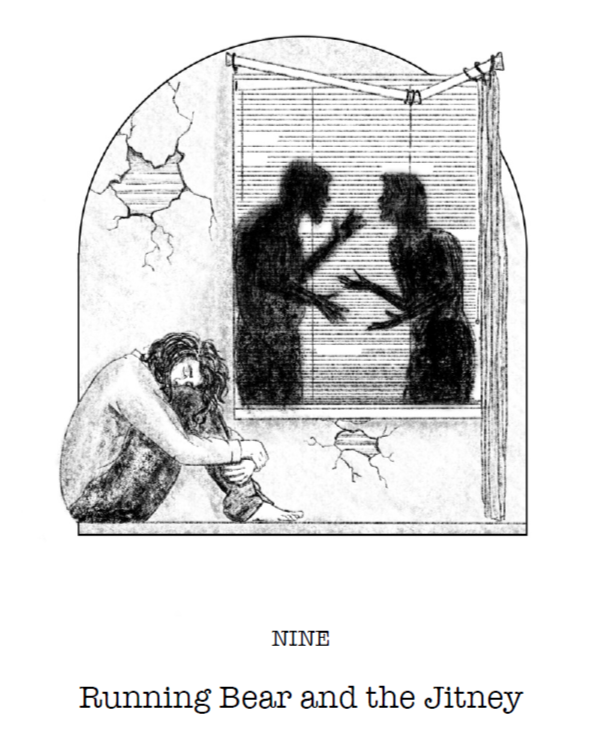

CROUCHED BENEATH the open window, your ears strain to hear fragments of a heated conversation. Agitated exchanges calm down to whispers after Ma says, “Hush, Wes. You’ll wake him.” How could she believe you sleep through these nightly bouts of venom slung back and forth across the porch? How could your perpetually agitated Iroquois mother fail to realize you inherited a measure of her disdain, or should you call it defiance? For months, you’ve known that little is going right and much is going wrong. The village, the few kids my age, the new fellow Pavel, everything’s haywire. Rivalries appear you never knew existed, with lines drawn that make no sense; lines you don’t get. And people look at you — kid of the mad scientist, as if you’re part of his plot to overthrow the order of things.

You long for the old days, embraces in the kitchen, the way the family surrounded you with love and rendered you secure and assured, the ordinary kid of mixed parentage that nobody used to notice. Now who are you? Running Bear — a half-breed with a ludicrous name, in Pavel’s words. You’re no longer a kindergartener nor a single-digit kid. But if you try to empathize with Ma and be as assertive and outspoken as she is, you could make things worse. Grow up. Stop your sniveling and get on with the life of a fourteen-year-old in this hollowed-out village. You and your dog walk alone along the river all the way to the confluence. You try to clear your troubled mind.

From your house at the top of Armitage Ridge, you can see the whole village in one sweeping glance: the big curve of the Shawnee River; the dam and falls at the mill; potholed roads along the river’s north and south banks; the narrow bridge over Mildred Creek to the road that splits the village in two; the little grid of narrow lanes with their partly restored houses with leaky roofs and sagging front porches; the towering Holmes Mill, its red metal roof, white clapboards, and broad grassy yard. Former commercial buildings at the northern outskirts, mostly abandoned, the exception being Pa’s workshop, a

former auto repair and tire shop. You stare across the mile or so from here to there and imagine the shabby village has taken to glaring back at you. You can see people coming and going; you imagine them casting looks and nods and cynical smirks at the sight of you. You take in their cunning.

You work at fitting in during lessons in the schoolroom. You are in a group that ranges in age from six to sixteen. Seven to ten kids on any given day — none your friends. You do the schoolwork to please Ma and Pa. Esteban, almost twenty, is the only boy who ever became a good friend. But he left classes three years ago to work on his parents’ farm. You fancy a girl, Samantha, who is a year older and pays you no attention. You fantasize stroking her silky black hair, your other hand on her cheek. Whatever. She’s out of reach. Her parents may have ganged up with others against you because they believe, in spite of how much they love Ma, that Pa is bent on toppling poor Ma as well as their presumptions about the future. Toppling Ma?

Pa often works late into the night. After dark, you lie there either hearing them argue, hearing more than you’d like, or waiting for the man to come home from the workshop. On one of those nights, you hear Mom’s muffled sobs down the hallway. Kayé, our big Newfie, gets up to clop across the kitchen for water. After she slurps, you hear her returning to her pad near the stove. Kayé means two in the Oneida language of the grandparents you never met. You were two when Kayé wandered into the family. Dogs in your grandparents’ tribe are guardians of other worlds, like the world you seem to be living in now. This is why you and Kayé are best friends.

You hear footsteps up the long path and the creak of the back door.

Pa’s work boots squeak across the kitchen. Lying awake waiting for the arguments to begin is agonizing, like bathing in a tub of cold water. You strain to hear their whispers. You wait attentively for the shouting, the tension, fearing that in your anticipation, you yourself are somehow bringing it on. You want to jump out the window.

What you hear leads to no good place. Pa is tired and edgy. He takes exception to Ma’s claim that Pavel has come to divert Pa from his good intentions, to steal from him and ruin our village. “Don’t bring Pavel into this,” he says.

“The man is a selfish boor,” Ma counters. It goes on like this and you learn that Pavel is an immigrant from someplace called Buffalo. Ma says he’s little more than a vagrant who wandered here after jumping ship downstream from Marietta. “It is rumored,” she claims, “that he made off with a stash of silver stolen on the paddle wheeler.” Her voice rising, she says that in Marietta, he worked out of what she called a brothel. “He was a vile pimp, Weston, a pimp!” Your vocabulary falls short and you can only imagine.

Pa yells back. “That’s a bunch of rubbish. Whatever Pavel did before is of no interest to me. He’s a hard worker and a good engineer.”

…