1

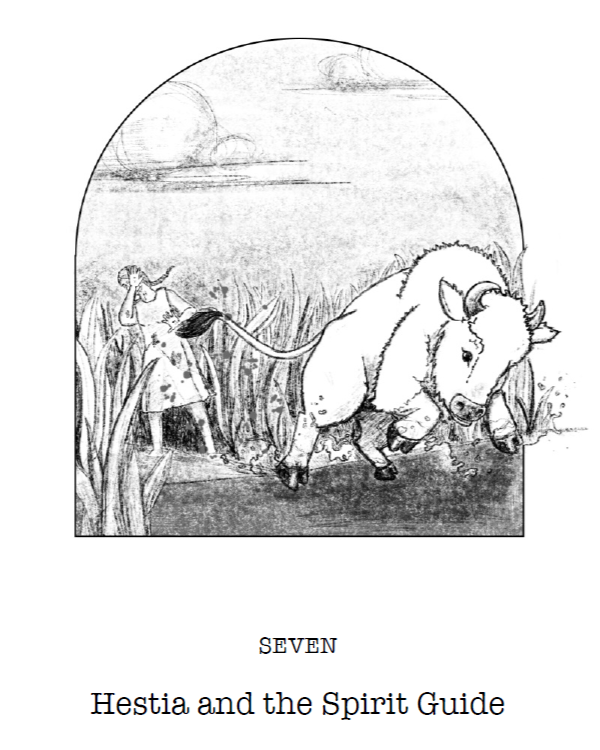

ONE MORNING WHILE PICKING the last of the huckleberries at the edge of an old field at the lakeshore, I saw a white bison lift his shaggy head above the shallow water and stomp his hoofs in the mud. I’d never seen a bison, let alone a pure white one. Startled by the sucking sound, I stood in awe at the size of him. I began to back away. He made a soft grunting sound and nodded his head as if to invite me to stay, his watery golden-brown eyes glowing with acceptance. I wanted this beast to trust me, to send loving feelings across the species divide. I needed love that morning and maybe he did too. Was I insane? My emotional instability was all wrapped up in a decision about whether to leave the only people I’d ever really known. I took

this ghostly creature to be a messenger.

Later that day in the library, I read that indigenous people believed that conversation with animals is a pathway to understanding and respecting the great circle, the ascendance of nature. One chief said, “If you talk to the animals, they will talk with you, and you will come to know one another.”5 Native people also regarded rare white variants, like my bison, to be sacred and thus untouchable. They projected ‘potent Medicine’. They were never hunted. Despite my innate pragmatism, I found this set of beliefs enhanced my sense of the possible. It stretched my world. On the other hand, was I so central in this bewildering world that a spiritually-potent animal would feel

compelled to appear as an omen to me?

After work, in conversation with Freya, the grandmother I most respect, she assured me that her world would not collapse if I departed, even though she understood that it would probably be forever. I was confused. To be loved by this grandmother was bedrock for me. But her blithe dismissal of my possible departure? Without her encouragement, I may not have grown up so self-assured and comfortable in Andeferas, our small village. Known as a precocious independent woman, I was also village librarian. I had a reputation for loving kids, thinking for myself, and speaking my mind at Village Council meetings. Freya, more than any other person, had nurtured my growth and comfort in this world. If I emigrated, how would I fit into a new place with strangers? Was the white bison’s Medicine drawing me toward unknown horizons or telling me to stay put?

The next day I found him farther from the lake in a vast meadow stretching to the western horizon. After bathing in the lake as the sun rose, I put on fresh clothing and strolled cautiously toward him. He paid me no attention until I got within twenty paces. Grazing in the tall grass, he looked up, his jaws rhythmically gnawing. From somewhere deep in his throat, he uttered rattling sounds. I moved within ten paces. He nodded and shook off insects buzzing his head. His tail whapped across his backside. I stepped closer, approaching him from the side as one would a horse. Though he outweighed me by many hundred stones, I felt no fear. I placed my hand on his head. He did not flinch. I reached up and gently scratched the forelock between his horns and cooed, “There, there. You are one very handsome spirit guide. I’ll say that.” He twitched an ear, shook his head slightly and moaned in appreciation. I backed slowly away, giving him space and the opportunity to graze again. He remained still, gazing at me as I turned and walked back

toward the lake.

In the following days I sought further guidance. I found him each morning, always within sight of the lake. Always alone. Two days before my prospective departure, I sat on a small mound watching the morning sky brighten across the lake. To my left, the white bison, some twenty-five paces away, looked up at me. He bleated a greeting. I called out, “Oh, if I leave this place, how I shall miss you.” Tears welled up. I buried my face in my palms, breathed deeply, wiped away the tears, and walked slowly to his side. I laid my palms on his shoulder. “Tell me, do I go or stay? Tell me.”

As the sun’s rays bled through the trees and lit up our patch of meadow, he responded with a monologue of grunts and moans. He went silent and looked into my eyes. I nodded my thanks. With nothing more to offer, he turned and trotted eastward, disappearing into the fog still clinging to the lakeshore.

***

Guided by the light of a waxing moon, Jason galloped into the village square just before midnight. The Argolians and I had been pacing aimlessly around the library. Jason dismounted, wobbly and exhausted. He did not acknowledge me or look my way. With his wide-brimmed hat, he batted away dust and sneezed. “Need somthin’ to drink,” he rasped. After chugging a stein of local brew, he reverted to his better manners and remained standing. “Thanks, I was really parched.” The rest of us sat in a semi-circle to hear what he’d discovered. The situation at the Brothers of the True Vine Sanctuary had worsened, he said, and therefore we must prepare for up to twenty women along with one or more monks and hopefully some children. The children hinge upon the so-far unsuccessful collusion of nursery staff. The women would be devastated, he believed, if they had to flee without their birthright kids. But if it came to that, they said they would still choose

to escape.

We agreed to gather in the square for departure by noon the next day. The Andeferas Village Council planned a going-off ceremony beginning with the pealing of the bells atop the former Methodist Church.

Early that morning I walked to the lakeshore. The white bison was nowhere to be seen. His absence marinated the silence. His disappearance into the fog yesterday was a moment I witnessed with certainty, a moment sodden with remorse. I felt strangely responsible. Thinking about it, I trembled at the portents that had begun to haunt me. From there, my mind went numb to the rising sun, the chorus of frogs and birdsong, the honeysuckle aroma of late summer. It was void of images, memories, names, truths. My guide was gone; my time here finished. Across the meadow, church bells rang. I rushed home to collect my belongings.

***